The Beat Goes On

‘Will you still need me, will you still feed me, when I'm sixty-four’ sang the Beatles on their 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Well, that was an awfully long time ago and the surviving band members – Paul and Ringo – are way past that milestone now. But our appetite for news and views of the Fab Four seems unabated and the latest attempt to satisfy it is a double helping of documentaries about the band’s relationship to India. The first, Meeting the Beatles in India is by an American, Paul Saltzman, while an Indian filmmaker, Ajoy Bose, is serving up The Beatles in India.

Saltzman first heard about meditation from a lecture Maharishi gave at New Delhi University in early 1968. Emboldened by promises of ‘inner rejuvenation’, he took the well-known pilgrim road through Haridwar up to the guru’s Academy in Rishikesh. But it was closed to outsiders, due to the arrival of the Beatles. Still coming to terms with the death of their manager Brian Epstein the previous August, while they had been on a meditation course with Maharishi in Wales, they had arrived in Rishikesh with wives and girlfriends to try to make sense of their hectic and confused lives. As McCartney remembers: “There was a feeling of: ‘It’s great to be famous and rich,” said McCartney, “but what it’s all for?’” Saltzman didn’t even know the Beatles were in India. He waited outside the ashram for eight days and then was taken to a small room where he was taught to meditate. His patience was amply rewarded, he says, by an experience of ‘bliss.’

Meeting the Beatles in India, with narration by Morgan Freeman, and contributions from cult director David Lynch and Beatles biographer Mark Lewisholm, will doubtless grab more attention than Bose’s film. It is a visually arresting and expansive work, but at its heart sits the smaller, affecting story of Saltzman himself. Now 78, he comes across as an endearing character, and perhaps it was this quality that led the normally wary John Lennon to allow him access to the coveted inner circle. “Maybe being in that altered state from having just meditated for the first time made a difference,” he says. “I think what they picked up immediately was: ‘This guy is not wanting anything from us.’” Saltzman had arrived at the ashram with few belongings. One of those was a Pentax camera. “In the week I spent with them,” he says, “I never thought of asking for an autograph, and I only took my camera out twice.”

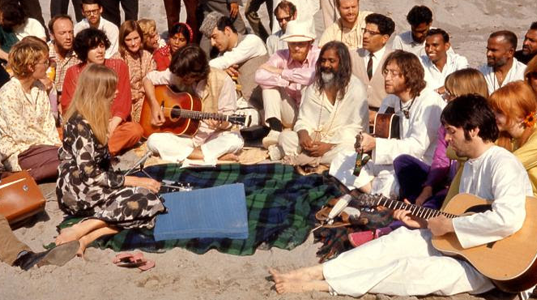

Those two outings yielded a rich harvest. Pictures forgotten about for 30 years show John, Paul, George, and Ringo hanging with fellow course participants Donovan, Mike Love of the Beach Boys, jazz flutist Paul Horn, Mia Farrow, and her sister Prudence, all in an unguarded and relaxed state, rehearsing new songs or just gazing contentedly out over the Ganges. The ashram’s benign effect was not to last; back home, the band soon reverted to the rock ‘n roll lifestyle of late nights, drug use, and interpersonal squabbles. But Saltzman’s photos beautifully captured an Indian oasis of tranquillity shared by four friends in a rare state of carefree contentment.

The second of the new documentaries, Ajoy Bose’s The Beatles in India, has a more expansive range than Saltzman’s. As Bose says: “You can tell the Beatles’ story so many different ways. I always felt that the India part of the Beatles saga was bigger than Rishikesh.” Because of this wider historical perspective, it may well prove to be the more enduring of the two records. The documentary charts a three-year journey, that starts from when George first picked up a sitar on the set of their film Help!, wanders through their brief sightseeing trip to Delhi in July 1966, and encompasses George’s friendship with sitar virtuoso Ravi Shankar and his recording of Wonderwall Music with classical Indian musicians in the Mumbai studios of HMV. And Bose doesn’t see the story as being primarily about Maharishi or meditation. “It’s about four working-class lads from Liverpool, who got deeply into Indian culture when George was the de facto leader of the group.” Maybe, but some of them got into it more deeply than others; when Ringo arrived in Rishikesh, he was so worried about the spicy food, he was lugging along a suitcase loaded with tins of his favourite Heinz baked beans.

Bose’s film gains from balancing the familiar tale with the equally fascinating story of how and why India fell in love with the Beatles. “I discovered them when I was about 12 or 13,” he remembers. “I was from the English-speaking Bengali middle-classes, who had been into Elvis Presley, Jim Reeves and Doris Day, and who were naturally bi-cultural. PG Wodehouse was our sense of humour, and that’s why I think there was an immediate connection with the Beatles: the wit. But my father was a bureaucrat who started with the British Raj,” he says. “His problem with the Beatles was that they didn’t behave ‘like Britishers’ – people with a stiff upper lip, who had short hair and didn’t let their feelings show. So the Beatles, with their long hair and jokes, really blew our minds.”

Today’s politically correct times are haunted by the spectre of cultural appropriation, but it is refreshing that Bose does not see any evidence of this. Indeed, he insists that what transpired was something closer to cultural exchange. “Osmosis on both sides,” he believes. “And look at the paradox. The Beatles were tired of the West’s commercialised capitalist culture and looking for spiritual peace, but we looked upon them as exciting symbols of modern culture.”

One unexpected highlight of Bose’s film is a cold war cameo. His newspaper research revealed that in 1968 left-wing Indian politicians were obsessed with the idea that Rishikesh was a CIA camp. The KGB even sent an agent there to find out what was going on. So we see footage operative Yuri Bezmenov reminiscing twenty years later how various “useful idiots from Hollywood” returned to the US to spread a pacifist message of “it down, look at your navel and do nothing”. As a faithful apparatchik, Bezmenov believes its contact with India demoralised American society, but Bose does not agree. He sees Rishikesh as being a positive influence for many reasons. Not only was it a huge boost to the band’s creativity – they returned to London with more than 30 new songs, most of which would end up on the 1968 White Album - but it gifted them a more philosophical outlook. They returned home more mature, as real individuals, but in a way, they never left India. George’s ashes were scattered on the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, and all these years later, the Beatles fan club is still growing in the subcontinent.

So what do the Beatles mean to a new generation of Indians? Bose is clear “Covid has changed our world, our reality over the past 16 months. Everyone is feeling so much more vulnerable and tired and I think the Beatles, in a very fundamental sense, still reconnect us with a sense of romance, a sense of joy, and a sense of innocence.”

For his part, Saltzman is in no doubt about the lasting legacy of those sunlit days when he innocently accumulated his lucrative archive of holiday snaps. Asked to pinpoint the highlight of it all, he is unhesitating: “Doing my first 30-minute meditation. It was fun meeting the Beatles, but that was secondary to the transformation of my inner life.”